Faythe of North Hinkapee: Read the first chapter NOW for FREE!

Sharing more about Faythe. As you know it’s live and launched and people are loving it.

Sharing more about Faythe. As you know it’s live and launched and people are loving it.

I now have over 200 reviews with an (impressive) 4.6 on Amazon and 4.4 on Goodreads.

I am also proud to say that the book has won several awards including a prestigious Pembroke (second place) award for Historical Fiction.

It is a historical fiction thriller set in colonial times and I am so excited to be able to share about it here. Talk about a – scary – Bruce Project outside my comfort zone, there are some chapters in there that made me blush to have written them.

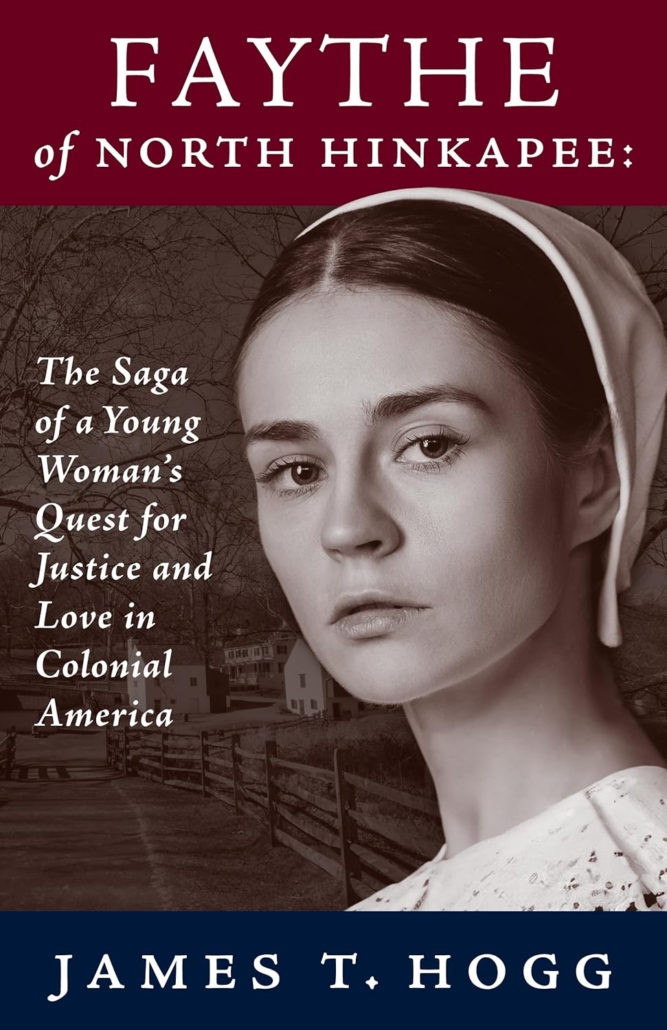

The book is titled: Faythe of North Hinkapee: The saga of a young woman’s quest for justice and love in Colonial America

I wrote Faythe under the pseudonym of James T. Hogg, which (of course) has its own website.

The book is historical fiction set in Colonial America during the Salem Witchcraft Trials. It is similar in genre to Ken Follett’s Pillars of the Earth, and if you enjoyed that epic tale, the odds are that you will like my story. My (only) goal was to write a true page-turner so that when the reader starts reading, they can’t put it down.

The book was published on March 12th of 2024 as an e-book and is now also available in paperback. I’ve been told that they can’t put it down once someone starts reading. So, using that to my advantage, I wanted to offer up the first chapter here for free. So without further adieu, I give you the first chapter of Faythe of North Hinkapee. If you get sucked in as I believe you will, you can buy the whole book here: https://bit.ly/3IojeLr and please do leave a review or come back and let me know what you think!

—

1677, SAGAWANEE LAND

INDIANS

“She can’t come with us,” said Passatan, chief of the Sagawanees. “Only my warriors will be with us when we kill the White Men.”

“Father,” said Katakuk. “If only you could have seen her with the bow and arrow. She bested all of—”

Chief Passatan interrupted, holding up a palm to his son.“I know of her prowess with the bow and arrow, and I’ve seen it many times, but there is much more to a death battle with the White Men. A man who loses has an honorable end, but a woman—you know what they will do with her and to her. She is your friend, and maybe more someday when the time comes. But this is not to be.” He looked at his son meaningfully but not unkindly. “This talk now must be over.”

Nununyi saw the look in Katakuk’s eyes and knew the answer before he spoke. He shook his head and looked down.

“It’s not fair,” he said.

Nununyi gazed at Katakuk—in his late teens and just coming into his full prowess as a man. He was tall and strong and lean, with muscles like the boulders carved smooth by the rushing icy streams, with a firm, flat stomach and long dark hair that he bound behind with a strip of leather. He walked with a litheness that spoke of inner strength, too. He would develop power and eventually leadership of the tribe. When Katakuk took the mantle from his father, they would have a strong leader.

She admired that he was proficient in all weaponry, including the tomahawk, the knife, the spear, the musket, and even the sword he took from a White Man in battle. He sometimes prevailed over even the mature men in hand-to-hand combat. She smiled a little as she thought, too, of the bow and arrow. Their people were known for that. He routinely bested others his age in marksmanship.

But he had never come close to Nununyi with the bow and arrow. No one could. Yet for some reason he had no jealousy that Nununyi outshone him in this. Instead, Katakuk carried great pride in her achievements. Katakuk recalled a recent conversation with his father, and his mother too. “Father. Mother. You should see her. Even the best of our men cannot come close to her with the bow and arrow. Nununyni with a bow and arrow is like watching a panther roam through the forest. She is beauty.”

Chief Passatan and his wife looked meaningfully at each other at the time. Is our son in love? the chief wondered, and with a warrior woman at that? He restrained himself from smiling, although this time he really wanted to. Chief Passatan almost never smiled, as he felt it inconsistent with being chief, but he had feelings, and a deep love for and pride in his son. Katatuk was quite aware of this and close-to-worshiped his father. So, despite Katatuk’s disagreement with his father’s decision, he would not go against him or undermine him; it was not his way.

Katakuk and Nununyi had been together since even before they could remember. At first it was just play, but then as they had grown up Nununyi had over time shown reluctance to do what women were supposed to do—cut up animals, cook, take care of babies, and deal with whatever the men didn’t want to do.

Even as a baby she had been fascinated watching others with the bow and arrow. And it was one of the first things she had learned as a young child, a labor of deep love from the start. Indeed, Nununyi neglected pretty much every woman’s duty she could, to the dismay and annoyance of her mother and the other women, all so that she could have time to fashion her bow out of a young sapling of just the right timbre, with the string made of the tendons of a deer or other animal, and then keep it well-oiled and clean. She joined the boys at the side of the stream, fashioning arrowheads out of stone pieces of just the right sort, and she gathered the perfect feathers that would guide the arrows in their flight.All could see that nothing transported Nununyi into joy more than when she let loose an arrow to fly to its target.

At first it was a novelty that the little girl child worked with the bow and arrow, but before she was even nine years old, she was bringing home game she had shot, and tribe members became more and more impressed. Later, she was at first decently competitive and then winning contests with adult men, and everyone began to be in awe. After her eleventh birthday, Nununyi never lost a single match. It seemed as if she never missed, and so it was.

But archery in a competition is one thing, thought Chief Passatan as he stirred the last of the embers in the community fire that evening. Tomorrow, some of us will die in battle. I myself might not be coming back. And I will not have a woman with us, distracting my son.

“Good night,” said Katakuk to Nununyi, holding her slim hand between his own as they prepared to part. “I have great sorrow that you are not coming.” He hung his head.

“Thank you, Kata,” she replied, using the affectionate nickname she had given him when they were toddlers and she had been unable to say the full name. “It is of no importance,” she insisted, with staid indifference.

Katakuk tilted his head and furrowed his brow as he studied her. What is she thinking? It meant everything to Nununyi to join with the men in the battle. She had told him many times before that she had been born to let fly her arrows to defend her people.

Perhaps she was saving face, then. He gave her the respect she needed, saying only, “Someday, when I am chief …”

She nodded and then said, “good night,” gently withdrawing her hand from his.

Someday, he thought, as he walked away, she will be my wife and she will be with me in many battles. Together we will kill the White People and drive them away. And she will also bear me sons who will be warriors. Over the years the two had moved from being inseparable childhood companions to finding themselves a young man and a young woman, with feelings for each other that had grown in intensity overtime.

Nununyi had at first not overtly revealed her feelings to him, even with his hints and encouragement. Katakuk realized that Nununyi preferred to be a puzzle to be solved—like the smooth carved wooden knots his grandfather had made for the amusement of them all. She refused to be an obvious conclusion. He had tried to return this conceit by doing his best to be a puzzle himself and keep her guess- ing. So he flirted with other girls from time to time, but he felt awkward and silly doing this, suspecting that Nununyi knew full well what he was about.

Finally, they had kissed, only that one time, and only a few nights ago. But that kiss had meant everything to Katakuk. He was indeed in love and now he could keep no secret of it from her.

She’s so beautiful, he thought, breaking off his musing, but then lingering on her beauty.

Her dark black hair and brown eyes framed a face that had only two expressions—impassivity and a smile so lively that it lit up those around her. She was small, so he had to bend down to kiss her, but her body had whipping power, explaining or resulting from her kinship with the bow and arrow. Although she was not at all vain, she spent a great deal of time with her hair, always braiding it and tying the braids together in back—it was anathema that her hair might get into her face and interfere with a shot. He dwelt a moment on the thought of her light, sinewy body that was yet fully that of a woman—and he squirmed with the thought of what it might be to be fully united with her.

Yes, Katakuk was in love with Nununyi; there was no doubt about it. And Nununyi was in love with Katakuk, although sometimes she wondered if she loved him more than she loved her bow and arrows. She thought about this now and then: I am in love with the man Katakuk, but my bow and arrows, they are me.

Nununyi nodded when Katakuk gave her the news, knowing full well everything Katakuk was thinking. She had expected this result andwas completely at peace. She knew exactly what she was going to do.

WHITE PEOPLE

“Jonesy,” said the big, bearish Gilbert Menon, the affectionate name rumbling deep in his voice, “it’s gonna be quite a dust-up tomorrow, isn’t it?”

John Jones, the smaller of the two and known for his stiffness, nodded matter-of-factly. “Yes it will.” Their spies had brought word that the Indian attack was imminent.

Both were in their early twenties, and the lumbering Menon was surprisingly swift in his strength. He was inordinately proud of his beard, his one touch of vanity, and he cut it every day, peering with his bright blue eyes into a shard of mirror he kept carefully wrapped in a pocket. He was otherwise careless of his appearance but always looked at other men as if he were measuring them up, which he was.

He’s a good man to have by you when it’s touch-and-go, thought Jones, glancing at his friend.

John Jones was of moderate height and “not thin or thick,” as an old man had once described him. He was a creative and devastating fighter and had killed many Indians in the eternal skirmishes, most of them with Menon at his side—they were mercenaries for the settlers. Jones’s hair was brown and he typically wore it long, though every few months when they emerged into a town he would find a barber to cut it short, and then he let it grow out again when they retreated back to the wilderness. His stiff personality was external, marking him as a man not to be trifled with. Inside, however, he was a man of passion and even love. He just had not found his soulmate yet. He knew he would … someday.

The two men were now veterans of many “dust-ups,” as they called them, with the Sagawanee Indians. They were too young and foolish to be really afraid of anything, and their good luck gave them not the slightest doubt that they would prevail in any battle.

Jones looked around at the score of other men they would fight alongside this time, all armed with muskets, spears, swords, knives, and some even with Indian tomahawks. They were a fearsome and fearless fighting force. The Town of Hinkapee had hired them through their leader Harriman Keep-Safe to drive off the Indians who had been harassing them consistently, and with increasing bloodshed—the death toll had risen on both sides.

Harriman Keep-Safe was a ruthless and pitiless man. He felt the best way to drive Indians away was to kill them, and as brutally as possible. After battles, he personally saw to it that any who were wounded died slowly and in the worst possible way. “Mercy”was not a word he knew. Jones shook his head at the thought— nothing good comes of it when a brutal man is in charge.

“What do you think about it?” Menon had askedJones one time after a particularly bloody battle. They were kindling a little campfire to roast a hunk of meat Menon had carved out of the leg of a horse that had fallen in the skirmish.

Four warriors had been wounded and left lying on the ground by their fleeing brothers, and they were struggling to breathe or to hold in their internal organs. Harriman had thrown two of them, alive, into the fire, watching impassively as they burned and screamed until death took them. The other two Harriman had tortured slowly and carefully. It had been clear that no one was to interfere.

“That way is not for me,” said Jones with a shudder inspite of himself. He threaded some meat on a stick and held it over the flame.

“Me, neither,” said Menon. “They’re just people like us. There’s a story I’m not sure I’ve told you. One time I was in a spying party and I got near one of their villages. I saw two of them. It was a boy Indian and a girl Indian, and he was talking to her. I couldn’t hear what he said, and I wouldn’t have understood it anyway, but clearly he was, you know, trying to talk her into doing what we all want to do with a girl. But she was cool with him, as girls can be. She smiled and giggled, but she turned him down. I knew right then that it was God who had put me there.”

“God—why God?” asked Jones.

“Because he wanted me to know that Indians are people like us.”

“I never thought of it that way,” said Jones, nodding in agreement. “But it makes sense.” He had never liked killing anyone, although he was a natural. It was too easy, and that worried him.

“I guess we should turn in, Jonesy,” said Menon. “Indians think they’re so wise, but they always attack in the darkest part of the night, just before sunup. They think we haven’t figured that out.”

“Yes,” replied Jones. He found himself inspecting the long knife that was always at his side.Without even thinking about it he had taken it out of its worn leather sheath and was running his finger ever so gently along the ever so sharp blade. It was special to him, a gift from his father. It had a handle that he found easy to grip, and the right weight for easy and facile use. And the blade was unfailingly sharp. Before a battle he found himself communing it. He shook his head to throw off the knife’s spell, Menon’s right, it’s time for some shut eye.

The group of twenty Indians crept up on the WhiteMen’s camp, which was quiet and dark. Good, thought Chief Passatan. They are asleep, and we will catch them unawares. He nodded to his left and to his right, where his son Katatuk sat on his horse, every bit the man he was becoming.All of them rode forward without hesitation, fearless in the faint starlight.

Indian chieftains did not lead from the rear, but instead from the front; accordingly, Chief Passatan offered the benediction of his heart: I am proud of my son.

This was his last thought before a musket ball tore through the top of his head, and he slowly, oh so slowly, fell to the ground. His horse, now riderless, followed the other horses and men forward in a rush at the sound of the shot.

No, the WhiteMen’s camp had not been sleeping after all. They were waiting, and it was a grim beginning for the Sagawanees. Three more warriors were quickly dispatched before the rest had dismounted and—armed, vicious, and fearless— struck out to take the battle to the White Men secreted in the trees.

The White Men’s advantage lasted only moments, because a musket fired, betrayed with sound and smoke the location of the shooter, and there was certainly no time to reload before the Indians closed with each musket man.

The battle was intense, every man fighting for his own life and to end the life of his adversaries. The Indians asked no quarter and gave none, either, and the White Men returned the savagery upon their foes.Screams of triumph mingled with death cries, as swords, knives, tomahawks, spears, and musket balls found their marks.

Katakuk had seen his father fall and thoughts ran through him all at once with the shock. What now shall we do? he thought in a panic. Am I now chief? What of the battle? Are we losing? But then there was no time to think, and he closed with an angry, enormous White Man who bore down upon him.

Katakuk ducked under the path of the White Man’s spear and rolled forward, coming up strong and hard with his knife. The look on the White Man’s face—his last expression, in fact—was surprise at the quick slicing of Katakuk’s knife up through his chin and into his brain, killing him instantly.

Suddenly, Katakuk, looking for his next opponent, was seized from behind and a knife came up to his throat.Instead of fear, he felt only sadness. I will leave now, having been chief for but a brief moment, but it was not to be. For some reason, the knife that would have left him bleeding like a slaughtered animal did not strike. Instead, the man holding the knife slumped to the ground.

Katakuk had a moment for a grim smile when he saw what had happened. An arrow had pierced the man in the head, an arrow with such vehemence, accuracy, and force that it had actually come out the other side. Nununyi In a flash he knew why she had not been upset at Chief Passatan’s forbidding her to come to the attack. She was coming anyway, and he felt a split second of pride and a thrill. But there was no time for reflection—another White Man was rushing upon him.

Arrows were flying from somewhere as another, and then another, and then another of Harriman Keep-Safe’s men went down. Keep-Safe traced carefully the direction of the arrows, and then concluded where they were coming from. He had one more musket shot left, and he took a chance and shot it into the trees where he could see the outline of the archer. It was a lucky shot and found its mark—the body jerked and fell. I’ll see about that one later, he thought, pulling his hatchet from his belt and running full tilt against another of the savages. No more arrows flew thereafter from that location.

The battle was over just a few minutes later, when the Sagawanees’ new chief gave the sign to his remaining fighters that it was time to leave. Although almost twenty Indian warriors had come to the battle, only seven were left, all of them wound-ed in some way. Katakuk’s body was whole, but his spirit was worse than wounded. I died, he thought, or came close to dying. But Nununyi saved me. And where was she? Katakuk pulled his horse under cover and bound it to a tree, then whisper-called to Nununyi in the direction from which she had shot the arrow that had saved his life. But all was silence in the woods. He crept out among his warriors—my warriors now! he thought, overwhelmed at the prospect that he was now chief. Am I ready? Gripping the shoulder of one warrior to ask about Nununyi, then staring into another’s face with what he hoped was an impassive plea for news of her, Katakuk felt panic for Nununyi. But he could hardly begin his reign as chief showing panic for his loss, so with as much steel as he could muster in a whisper, he roused his men for retreat, hoping the Nununyi would make her wayback – in secret – the way she had come.

As they rode away silent, into the trees, his heart sank as waves of grief washed over him.

Father, oh Father, what a terrible day! he wailed internally and wordlessly. Oh, Nununyi. My Nuni. Where are you?

But there was no time for grief. They had clearly lost this battle and now they had to get away with the few who were left—as their chief, he must care for them.

In seconds the Indians had melted off into the trees, found their horses, and galloped away.

Jones also thought that his troop had lost the battle.Out of their twenty men, almost ten had been killed outright, and of the ones remaining, almost all had severe wounds, which would no doubt claim at least two or three more of them. In the end it was the typical result of an Indian battle. It was a terrible war of attrition that never ended.

He and Menon had been fighting back-to-back, protecting one another from being struck from behind. It was Jones’s idea many months before, but Menon had taken to it instantly, and it had worked well in every battle. This day they had each dispatched an Indian warrior, Menon with a sword and Jones with his knife, their muskets long since discharged and thrown aside.

Menon and Jones, however, had only superficial cuts and bruises.They would need some medical attention when they got back to Hinkapee, but they’d soon be fighting again.Such was their fortune.

“You!” shouted Harriman Keep-Safe at Menon and Jones.“Gather up the wounded Indians and bring them here. Near the fire.”

Jones wrinkled his nose in disgust. He knew what was next.He looked around the camp and counted three Indians wriggling in the dirt. He looked at Menon, who shook his head.

“A quick death?” Menon asked.

Jones nodded. Together they walked over to the firstIndian. He had a stomach wound and his entrails were leaking out of him. He had only minutes to live, no matter what. Jones’s eyes met the other’s for just a second. Was it hatred or respect that passed between them before Menon’s sword came down, severing the man’s head from his body?

Harriman was shouting, but they hurried to dispatch another warrior, quickly and painlessly. “I’ll have no part in torturing anyone,” growled Menon.

Jones nodded wearily.Then suddenly, and even to his own surprise, he was say- ing, “This is my last battle.I don’t want to do this anymore.”

Menon shrugged. “Fine with me.Then what’ll we do?” But then he stiffened, and Jones heard the same rustling in the bushes. “What’s that?” Menon whispered.

They cautiously parted the leaves and branches to see what was making the sound, and Jones caught a glimpse of deerskin, long black hair, and a graceful bow still clutched in her hand where she lay.

“It’s a girl Indian!” he exclaimed. “She must be—must have been—I guess … the one that shot down three of our men.”

“Must be,” said Menon. The dawn was moving from gray to rose and they could see the girl’s body was still. But she had made the noise, and the blood was pulsing out of her. “I’ve never seen anyone so beautiful,” he murmured.

Jones laid his hand on her warm cheek. She was still alive, but she wouldn’t be if Keep-Safe knew about her. What horrors he would wreak upon her!

The men looked at one another. The two had become such close friends they almost thought as one.

Menon had knelt next to her and looked up at Jones and said, “Will you help me?”

Back among his people, Katakuk had to carry to his mother and the rest of the people the news of Passatan’s death. As they’d retreated from the scene of battle, the warriors had retrieved the body and reverently draped it over a horse, and a warrior was chosen to trot alongside—he would soon escort the fallen chief into their midst. At dawn, the silhouette of burdened horse and man became visible to all Passatan’s people, who were waiting to receive him. Most had lost fathers and sons and husbands and brothers, but all had lost their father, their chief, Passatan.

Katatuk’s mother covered her face when she heard the news and then walked into the forest to be alone with her thoughts, remembering the man she loved.

And Katakuk realized now that he had also lost Nununyi. None at home had seen her; none had spied her beautiful body among the fallen at the site of the attack. As soon as he could decently do so, Katakuk had returned to the scene of battle and scoured the woods. There was no sign of her, nor of her bow.

But in the White Men’s campfire were human bones.

——

Read more about the book at https://www.jamesthogg.com/

Buy the book on amazon and leave a review if you enjoy it here: https://bit.ly/3IojeLr